O maior poeta da geração beat, o potente Allen Ginsberg (1926-1997), enquanto vivo se envolveu nas lutas pela legalização da cannabis nos Estados Unidos da América.

Martin Torgoff, autor do livro Bop Apocalypse: Jazz, Race, the Beats, and Drugs , lançado em 2017 pela Da Capo Press, uma subsidiária do Hachette Book Group Inc., conta histórias do lendário escritor.

A primeira vez que experimentou cannabis, Allen Ginsberg estava dirigindo um carro em New York, com Walter Adams, um amigo da Universidade de Columbia, no Upper West Side de Manhattan. Ele começou a perceber o quão alto estava porque as ruas e as pessoas estavam se transformando em uma vasta megalópole robótica que parecia estar dentro de um grande firmamento de luzes brilhantes piscando, e ele começou a sentir que estava flutuando em um universo sem limites.

A princípio, o jovem, Ginsberg ficou assustado com a rapidez e a radicalidade das mudanças em sua percepção do espaço e do tempo. Ele se sentia desesperadamente perdido em um lugar que conhecia bem, e apenas estacionar o carro parecia uma prova titânica.

Quando finalmente estacionaram o carro e entraram em uma sorveteria antiquada na esquina da rua 91 com a Broadway, sentaram-se a uma mesa e ele pediu um sundae preto e branco. Quando apareceu – “este grande monte de sorvete parecido com a neve, mas absolutamente doce, puro, limpo e brilhante” – ele não conseguia acreditar em seus olhos, mas, por melhor que parecesse, não era nada comparado ao que aconteceu quando ele pegou seu colher e coloque um pouco na boca. A calda de chocolate quente havia se tornado um doce mastigável no creme gelado de baunilha, e cada molécula deliciosa parecia detonar em sua língua.

“Que sabor incrível! Acho que nunca apreciei verdadeiramente a invenção extraordinária de um sundae de sorvete preto e branco – e como era barato também!

E então, quando Ginsberg percebeu a infinitude do céu azul e olhou pela janela de vidro e viu o rio da vida fluindo – as pessoas passeando com cachorros, sorrindo, rindo, chorando – ele experimentou um momento de profunda sincronicidade e bem-estar. sendo, “tudo perfeitamente alegre e alegre”.

A cannabis tinha sido muito mais divertida e interessante do que Allen Ginsberg jamais esperara, e ele começou a pensar em como poderia aplicar o barato a outras experiências.

Na época, ele estava fazendo um curso de arte em Columbia e ficou curioso para ver o que aconteceria se visse as pinturas de Paul Cézanne no Metropolitan Museum of Art naquele estado de espírito. E assim ele fez.

Ao ficar olhando para as pinturas, ele percebeu que começou a entender o uso do espaço e da cor pelo artista de uma maneira que nunca havia feito antes – a maneira como as cores mais quentes as cores pareciam avançar em sua direção e as cores mais frias recuavam. Era um novo tipo de “consciência óptica” de parque de diversões que Ginsberg e Jack Kerouac, outro expoente do movimento beatnik, mais tarde chamariam de “chutes oculares”.

Pode-se reconhecer facilmente, na experiência de Ginsberg com aquele sundae preto e branco, um antegozo do deleite gastronômico que milhões descobririam mais tarde depois de fumar e sentir “a larica”. Pode ser que aquela busca por aquele litro de sorvete em noção de “chutes oculares”, tenha gerado os fundamentos estéticos dos shows de luzes psicodélicas da década de 1960.

Mas, claro, tudo isso estava a décadas de distância. Pouquíssimas pessoas fumavam cannabis naquela época, anos 50, e quando Ginsberg usava a erva e andava sozinho pelo campus da Columbia University, ele sempre tinha uma consciência aguda e desconfortável de ser o único naquela população de 20.000 “acadêmicos inteligentes” que por acaso estava em esse estado particular de consciência.

Além do “medo e tremor que viriam apenas da sensação de estar maravilhado com a grande enormidade em que eu estava, apenas fumando e alterando a mente e estando no universo”, ele começou a entender o “simplesmente paranóia que estava ligada a explorar o desconhecido ilegal….

Lembre-se, sempre havia a associação do que a sociedade estava impondo sobre você, a noção do ‘viciado em drogas’. o que significava ser um demônio, que é uma distorção da realidade muito estranha, horrível, quase ficção científica, perversa e diabolicamente cruel.

De longe, o que mais perturbou Ginsberg foi perceber como essa substância que poderia expandir sua consciência e realmente transmitir algo educacional havia sido tão demonizada por “essa gigantesca máquina oficial de propaganda do governo chamada Federal Bureau of Narcotics, porque você a encontrava na mídia e em todos os lugares.”

Mas, tão intensamente ciente quanto Ginsberg estava do tipo de problema em que poderia se meter, isso não iria detê-lo – “o que tinha a oferecer superava em muito os perigos, ao que parecia” – e foi quando ele, seu amigo artista e escritor, William S. Burroughs, junto com Kerouac, começaram a colocar benzedrina em seus chicletes e a fumar maconha quando conseguiam, e indo até a Times Square só para ver o que aconteceria.

A prisão de Neal Cassady por posse de três cigarros de cannabis em San Francisco, em 1958, e a supressão do livro ´Almoço Nu´, de Burroughs, foram toques de clarim que prenunciavam todo o ativismo de Ginsberg nos anos 60.

Prior to Cassady’s arrest, Ginsberg had only written about drugs. From then on he began to speak about them publicly, using his fame as a poet to publicize his views. He also recognized the need to back up his opinions with facts and began compiling his legendary drug archives: “I started the archives when the Beat Generation started to become a public issue – and that included the drug aspect and distortions of the history of women. drugs. as well as the distortion of the Beat Generation.”

Aside from the Cassady arrest, the other event that turned Ginsberg into the “original cannabis culture warrior, an anti-cannabis demolition team determined to shake the foundations of cannabis prohibition,” as Martin A. Lee, author of Smoke Signals , the Flame was his 1961 appearance on John Crosby’s CBS TV talk show, along with guests Ashley Montagu and Norman Mailer.

“We were going to discuss the modern sensibility and maybe a touch of ‘Beat’ or ‘hip’ and what that meant on television. I had lunch with Mailer earlier and said I would like to raise the issue of marijuana decriminalization or legalization. He said it would be silly because we would never get anywhere with this; it would just be considered shocking. But I said something about it when it appeared on the show, and when I did, Ashley Montagu added that he thought I was right, there wasn’t much of a danger with cannabis, and that he thought the government’s story about it was wrong . Then Mailer added that he had “tried it somewhere” and that was fine; and then Crosby, the host, added that he had tried it safely in Africa,

The FCC immediately intervened and forced Crosby and CBS to run a seven-minute rebuttal of the Department of Narcotics that denounced guests for their views. Both Ginsberg and Crosby were angered by the rejection, which was carried by the network as a public service announcement. Doesn’t a citizen’s right to free speech also apply to the kind of public television discussion about marijuana in which he has engaged?

“What made me most indignant was, first of all, the government’s presumption of taking over the radio waves in that way – they couldn’t do that now”, he said years later. “What right did the FCC have to object to our suggestions about changing a law? But back then, people were scared to death of the subject itself, which is why Mailer was so hesitant and hesitant to even touch it. He smoked cannabis and had a lot to lose from the scrutiny of that aspect of his life -just like the rest of us-so it was n’t just a matter of censorship; it was a question of the kind of fear that self-censorship breeds, and it was huge. It was censorship to the point where you couldn’t even open your mouth on television without being hit back by the government.”

What Ginsberg did next would have a major impact on his life for years to come. “I wrote a long, long letter to Harry Anslinger [Commissioner of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics], promising to get him. I called him a bastard and presented a long catalog of duplicity and lies that they had been promoting for so many years.”

In essence, the letter was a bold declaration by Ginsberg of his passionate intention to pursue the legalization of cannabis in the United States through political means. No one knows exactly how Anslinger reacted to the missive, or whether it prompted the FBI to open its long file on Ginsberg. Clearly, the Federal Bureau of Narcotics didn’t get many such letters in those days, and sending one like this was not only a bold move, but an unwise one to do, especially if the person was a gay Jewish beat poet who smoked cannabis , as said Allen. Ginsberg was. From that moment on, the bureau and the local NYC drug enforcement would look for a way to set the poet up for a cannabis bust.

“When I received my Freedom of Information Act material all those years later, I found that as of the date of John Crosby’s broadcast, following any suggestion that cannabis was legalized — by anyone — entered my file. For about three or four years, around the early ’60s, if someone expressed that notion in public, in any way, it would go into my archive. So yeah, I had a pretty big file. It was amazing.

Ginsberg was already well aware that any concerted effort to legalize cannabis in the United States would be an uphill fight that would have to be fought on many levels. On the one hand, it would have to face all the scientific, medical and sociological myths about the effects of weed that have been built up since the 1930s, which have become so deeply ingrained in the public mind that they have been blindly accepted as truth by an overwhelming majority of the population. Americanpopulation. On the other hand, he would also have to go against what weed came to represent in the public mind and, in that sense, he would have to deal with an image.

This part of the campaign would have to be, in effect, a public relations campaign designed to combat what Ginsberg believed to be 30 years of misinformation—to remove precisely what New York Times book critic Gilbert Millstein called “the stigmas of easily recognizable” and thus make their decriminalization and legalization more plausible.

In Ginsberg’s view, as surely as Gandhi had to confront the British imperialist mentality to achieve India’s independence, such a move would run up against the walls of some of the basic assumptions of American culture, society and politics.

As early as the late 1950s and the advent of the Beat Generation, the notion was circulating that cannabis was not only harmful in itself and would lead to harder drugs, but that it could induce a “defeatist” sensibility in the population towards the Cold War . People across the political spectrum believed that cannabis could weaken people’s will to resist communism just as easily as it could devitalize Americans’ willingness and ability to work, produce, and consume goods and services, which, in a car economy, rapidly expanding markets and domestic products would be equally catastrophic—the real bane of the American way of life.

The files that Allen Ginsberg began compiling, which would become a significant part of his personal archive at Columbia University’s Butler Library, were composed of numerous yellowed clippings of newspaper articles, copies of reports, and underlined and dog-eared oral studies. , testimonials – anything he could get his hands on, not just cannabis culture, but every drug in the illicit pharmacopoeia. If he saw a newspaper article about someone – like Cassady – sentenced to an outrageously draconian prison sentence for a small amount of cannabis, he would cut it; any information he could find, any evidence of government fraud, police corruption, the machinations of politicians, the inaccuracies of the media, the manipulations of scientists and researchers,

He was particularly interested in people who would speak honestly about their experiences with cannabis – people who could tell the true story of its use and underground culture, as Mezz Mezzrow had done in Really the Blues, and could describe the short-term and long- term effects. .

Nothing like an independently compiled sociological record of cannabis use has existed in the United States since the 1944 La Guardia Committee Report, which became almost impossible to locate. Little else existed other than isolated fragments about cannabis in academic and medical literature in a few university libraries; information compiled on individuals by narcotics squads; some intelligence on smuggling and records of arrests in police departments; and the self-serving statistics of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics.

What began to accumulate in Ginsberg’s East Village block in the late 1950s, first in Manila folders, then cardboard boxes, and finally large iron filing cabinets, was a remarkable record of government repression of a part of its population that would only grow progressively over the years – the counterweight to the lies and myths that Anslinger compiled to launch the crusade against cannabis in the 1930s.

“Almost everyone has tried [cannabis] and tried to write something about it. It’s all part of his poetic, no, metaphysical education of him. In Ginsberg’s view, drugs would be “a cutting edge issue – one of the fundamental ways in which we define ourselves as a people in the second half of the twentieth century”.

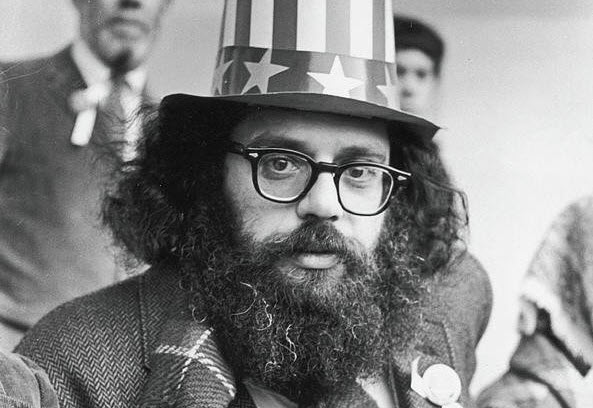

Allen Ginsberg always saw the Beat Generation as a “defining moment in the American conscience”. As he fulfilled his destiny as an epic bard and became one of the most famous American poets of the 20th century, he remained focused on drug use and how it could affect consciousness, creativity, and culture. He also remained a passionate advocate for changes in drug laws and policies.

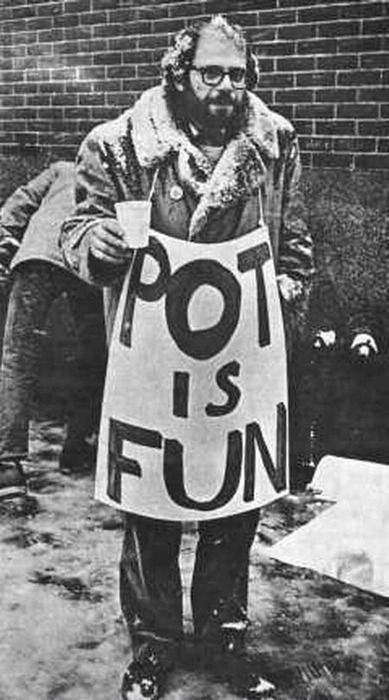

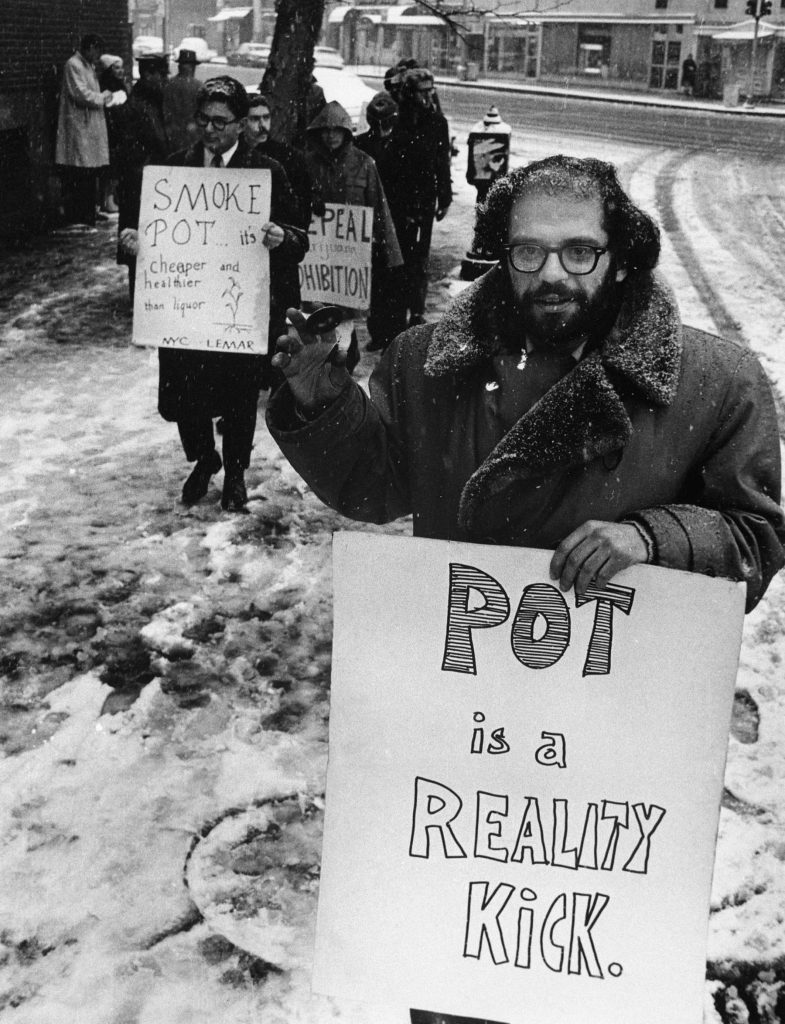

On a snowy December day in 1964, Allen Ginsberg made good on his promise to defy Harry Anslinger and the Marihuana Tax Act by appearing in Lower Manhattan with a small group of activists carrying signs that read “Pot Is Fun” and “Pot Is a Reality “. Bingo. The group Ginsberg formed with Ed Sanders was called LEMAR (for “Legalize Marijuana”) and it marked the beginning of the campaign to legalize cannabis in America.

Follow our reports on this and other topics. We are a magazine and platform dedicated to worldwide coverage of all things cannabis.

Quality information responsibly. We don’t make apologies.